Vancouver student gets to the root of why it’s so hard to put down your phone

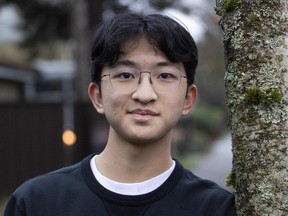

Henry Chuang, a Grade 10 student at St. George’s School in Vancouver, is now a finalist in a global science competition

By Denise Ryan

Last updated 12 hours ago

You can save this article by registering for free here. Or sign-in if you have an account.

“Everyone has been here: scrolling on social media instead of doing work … ”

Subscribe now to read the latest news in your city and across Canada.

- Unlimited online access to articles from across Canada with one account.

- Get exclusive access to the Vancouver Sun ePaper, an electronic replica of the print edition that you can share, download and comment on.

- Enjoy insights and behind-the-scenes analysis from our award-winning journalists.

- Support local journalists and the next generation of journalists.

- Daily puzzles including the New York Times Crossword.

Subscribe now to read the latest news in your city and across Canada.

- Unlimited online access to articles from across Canada with one account.

- Get exclusive access to the Vancouver Sun ePaper, an electronic replica of the print edition that you can share, download and comment on.

- Enjoy insights and behind-the-scenes analysis from our award-winning journalists.

- Support local journalists and the next generation of journalists.

- Daily puzzles including the New York Times Crossword.

Create an account or sign in to continue with your reading experience.

- Access articles from across Canada with one account.

- Share your thoughts and join the conversation in the comments.

- Enjoy additional articles per month.

- Get email updates from your favourite authors.

Create an account or sign in to continue with your reading experience.

- Access articles from across Canada with one account

- Share your thoughts and join the conversation in the comments

- Enjoy additional articles per month

- Get email updates from your favourite authors

Sign In or Create an Account

That’s the opening line from a video made by Henry Chuang, a Grade 10 student at St. George’s School in Vancouver. Chuang noticed he had a recurring habit of going on social media and procrastinating. He didn’t want to, but he was “stuck.”

It was impacting three major areas of his life: his studies, his cross-country running and the artwork he does in his spare time.

tap here to see other videos from our team.

“I didn’t want to keep scrolling, but my mind was getting tricked into it,” said Chuang.

So he decided to try to crack the code of why he kept falling into the same trap.

Now, Chuang’s short two-minute video on the problem — one that affects anyone with a smartphone, no matter their age — is one of 16 finalists for the 11th annual Breakthrough Junior Challenge, an international competition that invites students between the ages of 13 and 18 to create videos that “bring to life a concept or theory in the life sciences, physics or mathematics.”

The finalists hail from around the globe and were chosen from more than 2,500 applicants. They were evaluated based on their ability to communicate science concepts in the most engaging and illuminating ways.

The top winner, who will be announced in early 2026, will receive a $250,000 post-secondary scholarship. Their teacher will also receive $50,000 and their school will get a new science lab valued at $100,000. The prizes are sponsored by foundations established by Sergey Brin, Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg, Yuri and Julia Milner, and Anne Wojcicki, as well as contest partners the Khan Academy and the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

Chuang isn’t focused on the prize. Like any kid his age, he’s still trying to get off his phone.

-

Advertisement 1Story continues belowThis advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

The fact that his videography skills were self-taught from YouTube videos illustrates a certain irony: he’s a finalist, in part, because he spent time on his phone.

What he wants to do is get the use of it under control.

In the video, Chuang unpacks what happens when work required to achieve a goal — whether short-term like studying for a test or long-term like his dream of starting an Instagram account that explores the intersection of beauty and science — conflicts with one’s impulse to scroll through social media.

“Each trigger of social media activates a brain region,” said Chuang.

Social-media architects rely on social-media triggers like notifications, vibrant colours and engaging storylines so users get a dopamine hit, explains Chuang.

When the dorsal anterior singular cortex clocks that goals and actions don’t line up, we experience cognitive dissonance, explains Chuang. To cope with the mental discomfort or anguish experienced by two conflicting beliefs, desires or goals, synapses fire and push the problem to the anterior insula.

“That alert hits the amygdala and, like an alarm clock, it starts beeping constantly, which turns up discomfort and guilt.”

Then the prefrontal cortex jumps in and “reframes it,” so it doesn’t seem so bad.

“This is called rationalization,” said Chuang.

The hippocampus joins the party, retrieving positive memories that make the rationalization feel true.

“The hippocampus is quite devious,” said Chuang. “It convinces your brain that social media actually helps you, not harms you.”

Then comes the comforting flood of dopamine.

The dorsal striatum, in charge of habit-forming circuitry, loves that dopamine flood, and this reinforces the bad habit.

This is called the cognitive dissonance loop, and it’s what keeps us stuck, explains Chuang.

So how do we overcome this?

“You have to get used to the discomfort,” said Chuang.

Meeting difficult challenges ultimately leads to the same dopamine rewards that social media does: getting things done that bring you closer to your goals also stimulates dopamine release, even though it seems harder at first.

“It’s something me and my friends talk about all the time,” said Chuang.

For Chuang, figuring out how to creatively illustrate the cognitive dissonance process in a video helped him understand the brain’s chain reactions. But he also knows the human brain’s response to social-media triggers — highlight reels, notification pings, bright colours, reward badges — won’t change just because you understand the process.

“You have to consciously apply interventions thousands of times every day,” said Chuang.

To help himself, he uses an app called One Sec, which helps control the impulse to mindlessly scroll by linking to social-media apps on his phone, and interrupting the urge to scroll by diverting attention and using interventions like encouraging a pause to take a breath.

But he isn’t encouraging the world to log off social media completely. He, of course, hopes people will watch his Breakthrough Junior Challenge video on YouTube.

After all, the ‘likes’ count, and the dopamine feels so good.