Vancouverites deserve to see the 3D models that reveal what the city actually has in store for their neighbourhoods

Douglas Todd: Why can’t Vancouver be like Toronto, one of many cities that provide access to data that can be easily used to create interactive 3D models that show precisely how new towers, apartment blocks and houses are going to alter the city?

By Douglas Todd

Last updated 52 minutes ago

You can save this article by registering for free here. Or sign-in if you have an account.

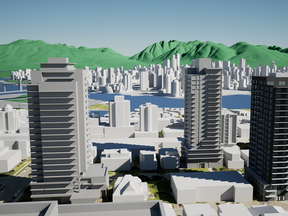

Much like a player of video games, Stephen Bohus can move effortlessly on his computer monitor through the three-dimensional digital model he has constructed of the streets, sidewalks and buildings of Vancouver.

Subscribe now to read the latest news in your city and across Canada.

- Unlimited online access to articles from across Canada with one account.

- Get exclusive access to the Vancouver Sun ePaper, an electronic replica of the print edition that you can share, download and comment on.

- Enjoy insights and behind-the-scenes analysis from our award-winning journalists.

- Support local journalists and the next generation of journalists.

- Daily puzzles including the New York Times Crossword.

Subscribe now to read the latest news in your city and across Canada.

- Unlimited online access to articles from across Canada with one account.

- Get exclusive access to the Vancouver Sun ePaper, an electronic replica of the print edition that you can share, download and comment on.

- Enjoy insights and behind-the-scenes analysis from our award-winning journalists.

- Support local journalists and the next generation of journalists.

- Daily puzzles including the New York Times Crossword.

Create an account or sign in to continue with your reading experience.

- Access articles from across Canada with one account.

- Share your thoughts and join the conversation in the comments.

- Enjoy additional articles per month.

- Get email updates from your favourite authors.

Create an account or sign in to continue with your reading experience.

- Access articles from across Canada with one account

- Share your thoughts and join the conversation in the comments

- Enjoy additional articles per month

- Get email updates from your favourite authors

Sign In or Create an Account

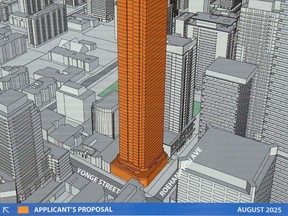

How will a new tower look from the air, from ground level and even from its interior? How will the highrise fit in, or not, with the existing neighbourhood? How much shadow will a new sixplex cast on adjacent dwellings?

The visual answers to these questions are there to see in the digital 3D images Bohus has painstakingly put together over weeks and months. He creates them from bits of property development data he manages to find on various City of Vancouver sites.

Bohus, a visual effects designer in B.C.’s film industry who also has a degree in landscape architecture, is far from alone in believing that one shouldn’t have to be a volunteer computer-graphics expert to learn how property developments are dramatically altering the look and feel of the city.

Why can’t the City of Vancouver be like Toronto and other cities?, asks Bohus. The country’s largest city provides its citizens with easy-to-find online access to free data from which it’s simple to create 3D working models of a proposed highrise or any other building.

And Toronto isn’t alone. For instance, Montreal, Calgary, Kelowna, Nanaimo and Victoria are among the cities that routinely provide citizens with access to data that can be used to create 3D “massing models.” In architecture, massing models are used to vividly reveal the overall size, bulk and impact of a future building.

For decades 3D imagery has been central to the property development business. There is arguably no better way for a designer, builder or client to envision what a new office building, apartment block or sixplex is going to look and feel like, and how, viewed from numerous angles, it will slot into its neighbourhood.

-

Advertisement 1Story continues belowThis advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

At one point, as Bohus showed the capabilities of the 3D models he has put together of Vancouver’s massive Broadway plan, he was able to navigate into the interior of an individual condo apartment in a proposed new tower. He showed the precise view, in colour, that the inhabitants would see of downtown Vancouver and the North Shore Mountains from their future balcony.

Such accurate models of proposed Vancouver buildings can take Bohus days to create from scratch. He does so by manually scraping the heights, widths and depths of proposed buildings off of developer’s two-dimensional plans, which can be found on the City of Vancouver’s website. In contrast, Toronto makes it easy.

“The City of Toronto has a digital 3D model and makes it available for free,” said Bohus, who studied with John Danahy, professor emeritus at the University of Toronto’s school of architecture and an advocate of government transparency and community engagement.

“For no apparent reason, the City of Vancouver fails to provide similar open data to its citizens. It’s created too many barriers to entry. It has to change. Open data is not a luxury. It’s central to government accountability,” said Bohus.

Through access to information requests, Bohus has frequently tried to get 3D data from the City of Vancouver. But each time, he said, the city avoids releasing the interactive 3D data it has on the thousands of new towers, buildings and homes it approves each year.

Bohus’s colleague, Randy Helten, a Vancouver sustainability advocate whose day job is as a language translator, said this is a crucial time for Vancouver voters “to be able to visualize the drastic changes city council and its planners have in store through their massive upzoning.”

Helten listed numerous decisions city councillors have made to speed up development approvals and hike density. They include the Broadway plan, which aims to make 500 blocks of the corridor into a “second downtown,” pre-approving sweeping zoning for fourplexes and sixplexes on single-family lots, and creating 17 new city “villages.”

Most importantly, Helten said, this March Vancouver city council is set to adopt “a 30-year official development plan that is entirely built on the premise that the public has been adequately informed and meaningfully involved in planning for the future of the neighbourhoods we live in. That’s a false premise.”

The City of Vancouver had previously told Postmedia News it can’t make available to the public the extensive 3D modelling that it uses internally, in part because it contains “sensitive information” from private companies.

But this week, asked why Vancouver isn’t as open with its data as Toronto, an official said in a statement: “The city sees clear value in 3D modelling as a public resource and is exploring how best to deliver this responsibly over time … pending availability of staff and resources.”

Helten, however, said it’s long past time for Vancouver to get up to speed: “This is 2026. And other cities are using this technology.”

An added reason 3D massing technology needs to be made available to Vancouver citizens, said Bohus and Helten, is that the city has in recent years almost completely eliminated its in-person open houses, at which the public was able to review developers’ building models.

Now virtually the only way citizens can find out about upcoming projects is from the city’s website. Typically, that amounts to an assortment of still images, many of them artistic renderings provided by developers, which give little sense of the mass of a new tower or sixplex. Such glossy renderings, architects have long complained, can often be misleading.

“As a public service,” Helten and others sometimes post Bohus’s 3D models of Vancouver development projects on their website, called CityHallWatch.

But Helten and Bohus believe voters shouldn’t have to rely on concerned volunteers. To emphasize their point, they remind Vancouver councillors that Toronto, a city that has long been Vancouver’s unofficial rival, is “winning” the contest of openness, accountability and authentic citizen engagement.

Get the latest from Douglas Todd straight to your inbox